MNIST Digit Recognition with a Multilayer Perceptron

Short update on SimX: the project is taking the backburner right now as I pursue different academic goals, I may return to it at a later date.

Neural Networks, briefly

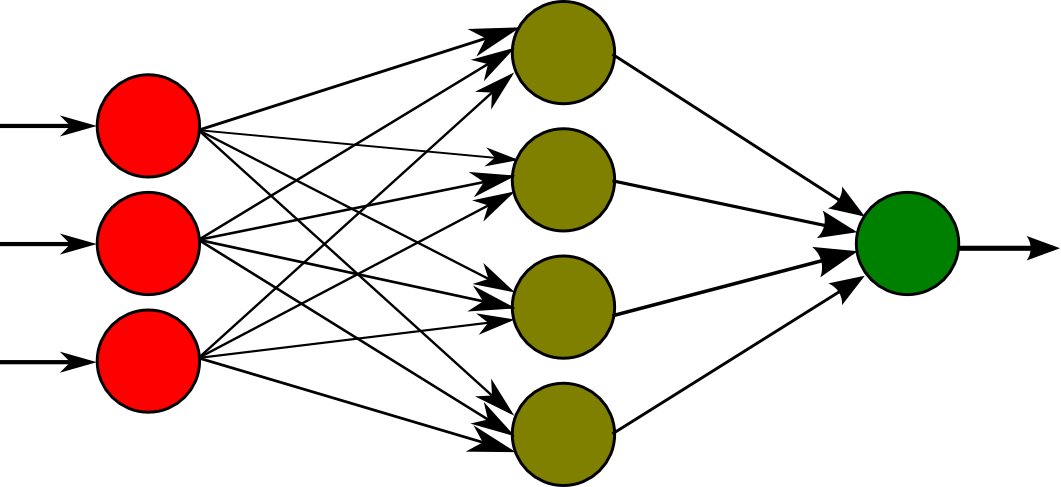

A few weeks ago I (re)stumbled upon these great posts from 3Blue1Brown on the topic of a neural network, or more specifically, a mutlilayer perceptron.

A representation of one is pictured above. Briefly, the way it works is that we encode some data numerically and pass it to the first layer of neurons, on the left. Between each of the layers is a connection between every neuron from each layer. These connections are weighted, meaning that each neuron in the next layer is a sum of the values of all the neurons in the previous layer times the weight of each of their connections. We also add a bias, or a constant term, to this calculation and finally use a sigmoid function to normalize the values to a value between 0 and 1. After performing these calculations on every layer, we are able to decode an output from the last layer of neurons.

We then train this network by using some input samples that have an expected output. By using a cost function that measures the difference between the expected output for some training example and some calculus, we are able to optimize the weights of all the connections and the biases to train the network to do almost anything. We can imagine the cost function as having an input of all the network’s parameters (weights and biases) and an output of the error. If we take the negative gradient of this multi-dimensional function, we are able to descend into some local minimum of the function that should (hopefully) do reasonably well on any problem.

3Blue1Brown and Michael Nielsen both explain this idea and the specifics behind it very well, and I highly recommend reading through their explanations if you have an interest in machine learning. Nielsen later provides a simple implementation of an initial and not fully optimized model to recognize digits in Python (in 74 lines!), and I hope to recreate it in C for the first part in this series. Eventually I want to refactor my code and iterate on the program to add features common in more modern machine learning models (hyperparameterization, regularization, etc).

The digits recognized are 28x28 pixels, with each pixel being a byte representing its brightness. The MNIST database provides a great set of training and testing data for this problem, with a total of 70,000 labeled examples (60k training + 10k test).

The complete running code for this program is on my GitHub repo.

Working in C

I haven’t used C prior to this project, and primarily have experience working in C++. I wanted to use C in this project to familiarize myself with it for my potential future projects in embedded development. Below I explain some of my decisions while creating this initial program.

Linear Algebra and Math

Plenty of math is repeated throughout backpropagation, often in the form of vector or matrix operations. Additionally, weights in the neural network can be stored as an array of matrices, and the biases can be stored as an array of vectors. I defined the following structs for vectors and matrices:

struct Vector {

int length;

double* elements;

};

struct Matrix {

int rows, columns;

double** elements;

};

I use pointers to double arrays allocatd by malloc to allow variable layer sizes. I restarted my implmentation of common vector and matrix functions many times while weighing the different ways to implement the functions.

/* Return Vector pointer */

struct Vector* add_vectors(const struct Vector* vector1, const struct Vector* vector2);

/* Return by Vector pointer argument */

void add_vectors(const struct Vector* vector1, const struct Vector* vector2, struct Vector* result);

/* Return Vector (automatic storage) */

typedef double (*binary_operation)(double, double);

struct Vector vector_binary_operation(const struct Vector vector1, const struct Vector vector2,

binary_operation operator);

void apply_vector_binary_operation(struct Vector vector1, const struct Vector vector2,

binary_operation operator);

double add_vectors(double a, double b) { return a + b; }

The first method requires allocating Vector structs on the heap through malloc. The downside to this is that every Vector being manipulated would be declared as a Vector* locally and arrays of vectors would become Vector**. When this type of variable is passed through a function to be modified (eg. array of bias vectors for stochastic gradient descent), Vector*** and Matrix triple pointers would conceivably be used, and I preferred not to deal with them. There is little ambiguity about how the function works, but performing multiple operations on the same vector would require storing (and allocating storage for) intermediate results. Furthermore, much of the iterating logic has to be repeated through the various functions (add_vectors and subtract_vectors would have a one character difference in implementation).

The second method of declaring functions allows in-place modification of either vector1 or vector2 by passing it as the address for the result vector. However, if a new vector is needed from any function, the user must allocate a vector of the correct size on their own to pass as a result pointer.

Most of the drawbacks above are avoided through the third method, at the cost of potentially some increased ambiguity. Rather than having separate functions for every operation, we pass a function pointer to a function that returns a double with two double parameters. Around this time I realized that allocating Vector as a local variable rather than on the heap is highly preferred, as we get a significant increase in speed. Because each vector is effectively 12 bytes (4 byte int length and 8 byte double* pointer), there is no risk of stack overflow and the rest of the program becomes much cleaner. I also define an in-place function that mutates the data of vector1.

typedef double (*unary_operation)(double);

struct Vector vector_unary_operation(const struct Vector vector, unary_operation operator);

void apply_vector_unary_operation(struct Vector vector, unary_operation operator);

Creating the equivalent functions for unary operations allows trivial implementation of functions that zero initialize a vector, initialize the vector with a standard distribution, or negate a vector. I implemented similar functions for matrices, as well as functions to multiply matrices by vectors, to transpose a matrix, and to compute the outer product of two vectors.

struct Vector matrix_vector_multiply(const struct Matrix matrix, const struct Vector vector);

struct Matrix matrix_binary_operation(const struct Matrix matrix1, const struct Matrix matrix2,

binary_operation operator);

struct Matrix matrix_unary_operation(const struct Matrix matrix, unary_operation operator);

struct Matrix outer_product(const struct Vector vector1, const struct Vector vector2);

struct Matrix transpose(const struct Matrix matrix);

void apply_matrix_binary_operation(struct Matrix matrix1, const struct Matrix matrix2,

binary_operation operator);

void apply_matrix_unary_operation(struct Matrix matrix, unary_operation operator);

A few math utilites are also defined for the neural network:

double generate_std_norm_dist() {

double irwin_hall_var = 0.0;

for (int i = 0; i < 12; i++) {

irwin_hall_var += (double)rand() / (double)RAND_MAX;

}

return min(1,max(-1,irwin_hall_var - 6));

}

double sigmoid(const double z) {

return 1 / (1 + exp(-z));

}

double sigmoid_prime(const double z) {

double ez = exp(-z);

return ez / ((1 + ez) * (1 + ez));

}

The functions above are used for common math operations (initializing the parameters and activation function). To generate a roughly normal distribution, an Irwin Hall distribution with six uniformly distributed variables is shifted to have a mean of zero, giving us a normal distribution. I truncate this distribution as well to improve performance later. sigmoid_prime is used for backpropagation when training our model later.

File I/O

Using the newly defined linear algebra library, I tackled file processing through the following functions:

int byte_array_to_big_endian(unsigned char* bytes) {

return (bytes[0] << 24) | (bytes[1] << 16) | (bytes[2] << 8) | (bytes[3]);

}

int read_image_file(const FILE* file, struct Vector** images) {

unsigned char* magic_number_bytes = malloc(4 * sizeof(char));

unsigned char* image_count_bytes = malloc(4 * sizeof(char));

unsigned char* row_count_bytes = malloc(4 * sizeof(char));

unsigned char* column_count_bytes = malloc(4 * sizeof(char));

fread((void*)magic_number_bytes, sizeof(char), 4, file);

fread((void*)image_count_bytes, sizeof(char), 4, file);

fread((void*)row_count_bytes, sizeof(char), 4, file);

fread((void*)column_count_bytes, sizeof(char), 4, file);

int image_count = byte_array_to_big_endian(image_count_bytes);

int row_count = byte_array_to_big_endian(row_count_bytes);

int column_count = byte_array_to_big_endian(column_count_bytes);

int pixel_count = image_count * row_count * column_count;

unsigned char* new_images_bytes = malloc(pixel_count * sizeof(char));

fread((void*)new_images_bytes, sizeof(char), pixel_count, file);

int vector_size = row_count * column_count;

struct Vector* new_images = malloc(image_count * sizeof(struct Vector));

for (int i = 0; i < image_count; i++) {

new_images[i] = create_vector(vector_size);

for (int j = 0; j < vector_size; j++) {

new_images[i].elements[j] = ((double)new_images_bytes[i * vector_size + j]) / 256.;

}

}

free(magic_number_bytes);

free(image_count_bytes);

free(row_count_bytes);

free(column_count_bytes);

free(new_images_bytes);

*images = new_images;

return image_count;

}

int read_label_file(const FILE* file, char** labels) {

unsigned char* magic_number_bytes = malloc(4 * sizeof(char));

unsigned char* label_count_bytes = malloc(4 * sizeof(char));

fread((void*)magic_number_bytes, sizeof(char), 4, file);

fread((void*)label_count_bytes, sizeof(char), 4, file);

int label_count = byte_array_to_big_endian(label_count_bytes);

char* new_labels = malloc(label_count * sizeof(char));

fread((void*)new_labels, sizeof(char), label_count, file);

*labels = new_labels;

free(magic_number_bytes);

free(label_count_bytes);

return label_count;

}

The byte_array_to_big_endian function is used to reverse the byte order to its endianness in the MNIST dataset. From there we read the different counts included in the file and iterate, converting the images to a normalized Vector and the labels to single bytes in a char*. As an aside, it would save a lot of space to simply store the images with a char** variable (each pixel is only one byte), but it would require translation into a Vector at training time to be easy to work with, and iterate through the entire training data several times, making it wasteful.

Neural Network

First I implemented the arguably simpler function that feeds forward through the network. With the linear algebra header files included, the code for feeding forward becomes very readable and makes memory management simple. I first initialize an activation vector to store the input data/activations of future layers, then perform three operations per layer: weight matrix multiplication, bias addition, and applying an activation function.

struct Vector feed_forward(const int layer_count, const struct Matrix* weights,

const struct Vector* biases,

const struct Vector* input) {

struct Vector activation = create_vector(input->length);

for (int i = 0; i < input->length; i++) {

activation.elements[i] = input->elements[i];

}

for (int i = 0; i < layer_count - 1; i++) {

struct Vector weighted = matrix_vector_multiply(weights[i], activation);

apply_vector_binary_operation(weighted, biases[i], &add_vectors);

apply_vector_unary_operation(weighted, &sigmoid);

free_vector(activation);

activation = weighted;

}

return activation;

}

At this point I realized I probably should have created a new struct to pass neural network parameters, but instead I dealt with this monster of a function signature…

void sgd(struct Matrix* weights, struct Vector* biases,

const struct Vector* training_images, const char* training_labels,

const struct Vector* test_images, const char* test_labels, const int test_size,

const int training_size, const int minibatch_size, const int epochs,

const int layer_count, const double learning_rate) {

int training_data_size = training_size;

int* labels = malloc(training_data_size * sizeof(int));

for (int i = 0; i < training_data_size; i++) {

labels[i] = i;

}

/* Iterate through different mini-batches */

for (int epoch = 0; epoch < epochs; epoch++) {

for (int i = 0; i < training_data_size - 1; i++) {

int j = i + rand() / (RAND_MAX / (training_data_size - i) + 1);

int t = labels[j];

labels[j] = labels[i];

labels[i] = t;

}

for (int i = 0; i < training_size / minibatch_size; i++) {

/* Allocate parameter change variables */

struct Matrix* nabla_weights = malloc((layer_count - 1) * sizeof(struct Matrix));

struct Matrix* delta_nabla_weights = malloc((layer_count - 1) * sizeof(struct Matrix));

struct Vector* nabla_biases = malloc((layer_count - 1) * sizeof(struct Vector));

struct Vector* delta_nabla_biases = malloc((layer_count - 1) * sizeof(struct Vector));

for (int j = 0; j < layer_count - 1; j++) {

nabla_weights[j] = create_matrix(weights[j].rows, weights[j].columns);

nabla_biases[j] = create_vector(biases[j].length);

zero_matrix(&nabla_weights[j]);

apply_vector_unary_operation(nabla_biases[j], &zero_vector);

}

/* Backprop through each training sample */

for (int j = 0; j < minibatch_size; j++) {

struct Vector image = training_images[labels[i * minibatch_size + j]];

struct Vector* activations = malloc(layer_count * sizeof(struct Vector));

activations[0] = image;

struct Vector* z_vectors = malloc((layer_count - 1) * sizeof(struct Vector));

for (int k = 0; k < layer_count - 1; k++) {

z_vectors[k] = matrix_vector_multiply(weights[k], activations[k]);

apply_vector_binary_operation(z_vectors[k], biases[k], &add_vectors);

activations[k + 1] = vector_unary_operation(z_vectors[k], &sigmoid);

}

struct Vector y = create_label_vector(activations[layer_count - 1].length,

training_labels[labels[i * minibatch_size + j]]);

struct Vector delta = vector_binary_operation(activations[layer_count - 1], y, &subtract_vectors);

apply_vector_unary_operation(z_vectors[layer_count - 2], &sigmoid_prime);

apply_vector_binary_operation(delta, z_vectors[layer_count - 2], &hadamard_product_vectors);

delta_nabla_biases[layer_count - 2] = delta;

delta_nabla_weights[layer_count - 2] = outer_product(delta, activations[layer_count - 2]);

for (int k = layer_count - 2; k > 0; k--) {

struct Vector sp = vector_unary_operation(z_vectors[k - 1], &sigmoid_prime);

struct Matrix tw = transpose(weights[k]);

delta_nabla_biases[k - 1] = matrix_vector_multiply(tw, delta);

apply_vector_binary_operation(delta_nabla_biases[k - 1], sp, &hadamard_product_vectors);

delta = delta_nabla_biases[k - 1];

delta_nabla_weights[k - 1] = outer_product(delta, activations[k - 1]);

free_vector(sp);

free_matrix(tw);

}

free_vector(y);

for (int j = 0; j < layer_count - 1; j++) {

free_vector(z_vectors[j]);

apply_vector_binary_operation(nabla_biases[j], delta_nabla_biases[j], &add_vectors);

apply_matrix_binary_operation(nabla_weights[j], delta_nabla_weights[j], &add_vectors);

free_vector(delta_nabla_biases[j]);

free_matrix(delta_nabla_weights[j]);

if(j>0) free_vector(activations[j]);

}

free(activations);

free(z_vectors);

}

/* Change parameters according to minibatch */

for (int j = 0; j < layer_count - 1; j++) {

for (int k = 0; k < nabla_biases[j].length; k++) {

nabla_biases[j].elements[k] *= (learning_rate / (double)minibatch_size);

}

for (int k = 0; k < nabla_weights[j].rows; k++) {

for (int l = 0; l < nabla_weights[j].columns; l++) {

nabla_weights[j].elements[k][l] *= (learning_rate / (double)minibatch_size);

}

}

apply_vector_binary_operation(biases[j], nabla_biases[j], &subtract_vectors);

apply_matrix_binary_operation(weights[j], nabla_weights[j], &subtract_vectors);

free_matrix(nabla_weights[j]);

free_vector(nabla_biases[j]);

}

free(nabla_weights);

free(nabla_biases);

free(delta_nabla_weights);

free(delta_nabla_biases);

}

int correct = 0;

double avg_cost = 0.;

struct Vector output;

for (int test = 0; test < test_size; test++) {

output = feed_forward(layer_count, weights, biases, &test_images[test]);

int ans = 0;

double cost = 0.;

for (int j = 0; j < output.length; j++) {

if (output.elements[j] > output.elements[ans]) ans = j;

cost += pow(output.elements[j] - (test_labels[test] == j ? 1 : 0), 2);

}

if (ans == test_labels[test]) correct++;

avg_cost += cost;

free_vector(output);

}

avg_cost /= test_size;

printf("Correct: %d/%d\tAccuracy: %f\tCost: %f\tEpoch:%d/%d\n", correct, test_size, (double)correct / test_size, avg_cost, epoch + 1, epochs);

}

free(labels);

}

The function is quite long as well. Way too long to be “good” code. I initially wrote it as three functions, one iterating over epochs, one iterating over a minibatch, and one performing the backpropogation for each sample. At some point I gave up when trying to decide how to pass and return parameters to each function. Refactoring this is definitely something I would consider in the future.

As I wrote, this function performs stochastic gradient descent. This critical function manages the iterative adjustment of weights and biases to optimize the network’s performance.

Key insights into the sgd function:

- It operates through a series of epochs, traversing the training data with shuffling via mini-batches, enabling diverse and randomized parameter updates.

- The function dynamically alters weights and biases using computed gradients scaled by the learning rate, a fundamental element in the pursuit of convergence and accuracy.

- Throughout each epoch, the function evaluates the network’s performance on test data, assessing accuracy and cost, offering essential metrics for monitoring the network’s progress.

- Efficient memory allocation and deallocation strategies are implemented, crucial for managing the dynamically allocated matrices and vectors, optimizing resource usage.

- Periodic output showcases epoch-wise progress, revealing accuracy, cost metrics, and the network’s learning behavior.

Debugging

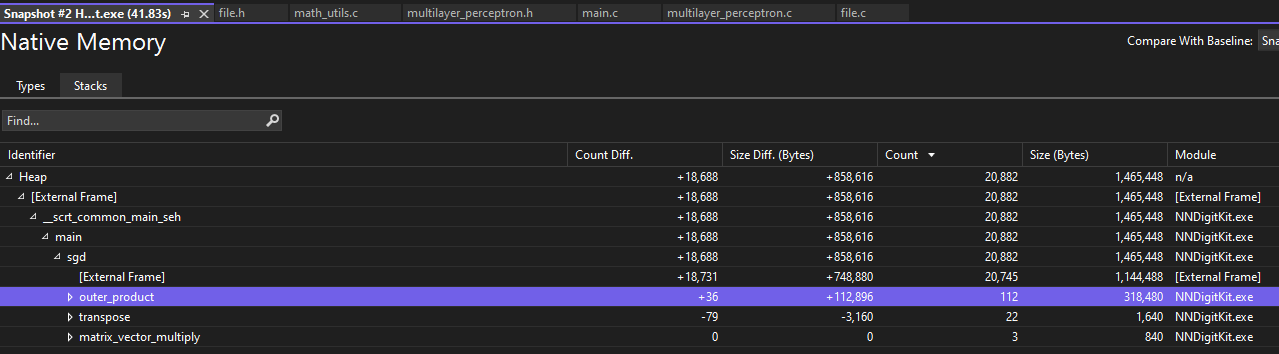

Eventually debugging this function when I completely finished it became much easier with Visual Studio’s tools.

Using snapshots of heap allocations, I can compare allocations and identify which identifiers relate to which allocations. This helped me easily pinpoint memory leaks without painstakingly tracking every allocation. I also was surprised by how much is optimized away by Microsoft’s C compiler in the Release build configuration compared to Debug; many of the variable values and allocations I attempted to check had been optimized away and couldn’t be debugged in the Release configuration.

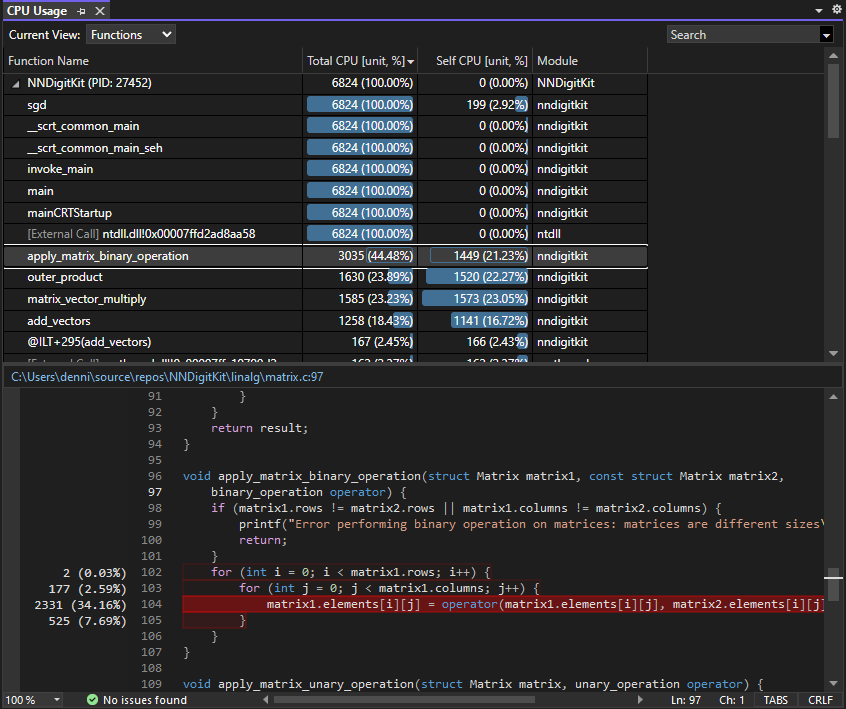

I was also curious about the CPU usage of my program, as it seemed to be around 5-6%.

Visual Studio provides impressive insight into CPU usage of C/C++ programs, breaking down CPU usage not only by function but by each line in each function. Performing element-wise binary matrix operations (addition, subtraction, etc.) was by far the most intensive function, highlighting the importance of AI accelerators and GPUs in machine learning training. I’m excited to use frameworks such as OpenCL or even CPU parallelization in the future to accelerate these operations.

As for the CPU usage, I at first thought that 6% seemed reasonable, as I was running this on a machine with 8 cores and 16 logical processors (1/16 ~ 6%). I ran the program in Release configuration as well, only get the same 3-6% usage. Strangely enough, running the executable outside of Visual Studio’s debugger showed 16% CPU utilization in Task Manager! Looking at the utilization graphs for each logical processor, 3 or 4 of the processors seemed to have very high utilization. Was the C compiler multithreading my program? I doubt the optimizations are that aggressive, and I think Windows is doing some interesting process scheduling that allows the program to run at such high utilization.

Results

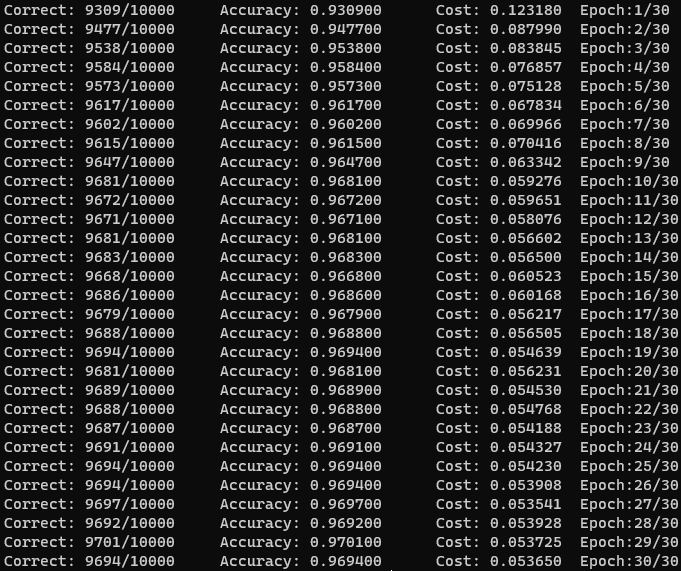

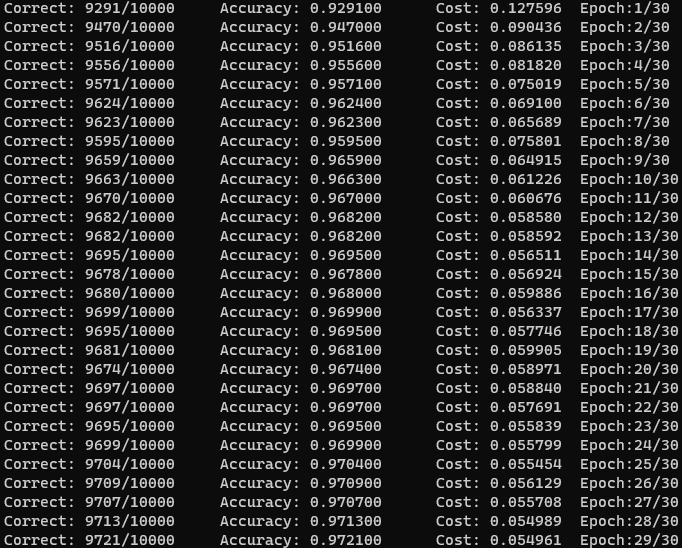

After trying several parameters, I had trouble getting the results I wanted and would get stuck with a cost around 1.0. I initially thought that some memory or parameter related bugs caused my program to struggle to start guessing values for the digits, but after debugging and printing out some of the tests, the program was making decent, albeit hesitant guesses. It took me a few hours of debugging to realize that increasing the number of epochs would significantly improve the accuracy of my network, and after re-reading Michael Nielsen’s code in Python, I realized that the epoch variable related to the number of times the network is trained on the entire dataset, not the number of mini-batches it is trained on… :)

After I ironed out that problem and some memory leaks, I was able to achieve around 93% accuracy on my network after only one epoch. The structure I landed on was similar to Nielsen’s, with a single hidden layer of 100 nodes, a learning rate of eta = 3.0, and a mini-batch size of 10. After 30 epochs, the accuracy plateaued at 97% accuracy.

I was pleasantly surprised by this, especially given that previous papers using two-layer neural networks were only able to reach a test error rate below 3% using deskewing or convolutional neural networks. Using a network structure similar to the paper (300 hidden neurons), I was only able to reach 70% accuracy.

I also wondered if this accuracy can be attributed to my use of double types to store parameters over floats. I decided to investigate this further and was surpised to find that using floats did make a measurable difference. The float model tended to lag behind a bit (<0.5%), but surprisingly was able to eventually beat the double model, with a total accuracy of 97.21%! Interestingly enough, the cost function over the test data is higher despite the increased accuracy. The error, being 2.79%, barely outperforms all standard three layer neural networks in the paper by LeCun et al. in 1998 (linked above).

A certainty of the usage of floats instead of doubles is that the memory usage is much lower. The float model used around 226 MB of memory in Debug configuration, compared to ~440 MB for the double model. For larger problems, there is definitely an advantage in using lower precision parameters when memory is a concern.

Conclusion

One of my biggest takeaways from this was respect for the authors of TensorFlow and other machine learning libraries. I was surprised by how slow the C implementation was, and can imagine the work needed to get networks like this accelerated by hardware. Implementation of this neural network is a good way to practice memory allocation, especially between all the matrix and vector operations being done. I hope this breakdown is helpful, and I look forward to potentially expanding on this project.